Writing in Nature, naturally

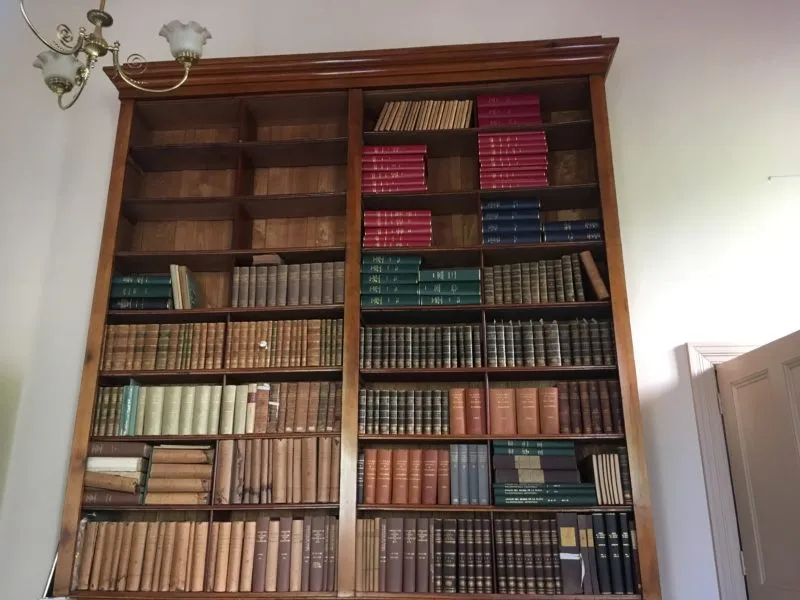

Scientell’s new home, the historic Royal Society of Victoria building, houses a stunning library that includes the first edition of the journal Nature. It’s clear that people communicated science in 1869 differently from now.

The first research article in that first issue is entitled, ‘On The Fertilisation Of Winter-flowering Plants’. Here is a paragraph from the author, Alfred Bennett:

‘During the winter of 1868-69, I had the opportunity of making some observations on this class of [winter flowering] plants; the result being that I found that, as a general rule, fertilisation, or at all events the discharge of the pollen by the anthers, takes place in the bud before the flower is opened, thus ensuring self-fertilisation under the most favourable circumstances, with complete protection from the weather, assisted, no doubt, by that rise of temperature which is known to take place in certain plants at the time of flowering.’

The writing is clear and evocative. The first person ‘I’ paints a picture of Alfred’s experiences as he strolled amidst the ‘hazel-nut Corylus avellana, the butcher’s broom Ruscus aculeatus, and the gorse Ulex europæus’.

Early scientific discourse favoured the active voice, which helps to make writing personal, clear and concise. An active sentence is one in which an agent (Alfred) does something (observed) to a person or thing (plants). For a passive sentence, the reverse is true – the subject has something done to it by an agent. Had he written in the passive voice, Alfred could have begun: ‘During the winter of 1868-69, observations were made on this class …’.

Subsequently, researchers decided that scientific writing needed to be objective, casting the observer as a disinterested, objective party recording dispassionately the behaviour of ‘objects, things and materials’ (Ding 1998). The passive voice distances the writer from the consequences of their actions and findings. Bart Simpson, for example, stating ‘mistakes were made’ is far from an admission that he has erred.

Scientific writing is now moving back to active voice. The Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, for instance, has the following piece of advice for authors on its website:

We will ask authors that rely heavily on use of the passive voice to re-write manuscripts in the active voice. While the use of the phrase “the author(s)” is acceptable, we encourage authors to use first and third person pronouns, i.e., “I” and “we,” to avoid an awkward or stilted writing style.

This is good advice. Active language is easier to understand. It is more like normal speech and makes clear who is doing what.

You can find that first Nature paper here.

References

- Ding, D., (1998) Rationality reborn: Historical roots of the passive voice in scientific discourse, in J.T. Battalio ed., Essays in the Study of Scientific Discourse: Methods, Practice, and Pedagogy, Ablex, Stamford, CT, pp. 117–135.

- Leong, P.A. (2014). The passive voice in scientific writing: The current norm in science journals. Journal of Science Communication, 01(A03), 1–16. Retrieved from jcom.sissa.it/sites/default/files/documents/JCOM_1301_2014_A03.pdf Google Scholar

Date Posted:

November 9, 2017